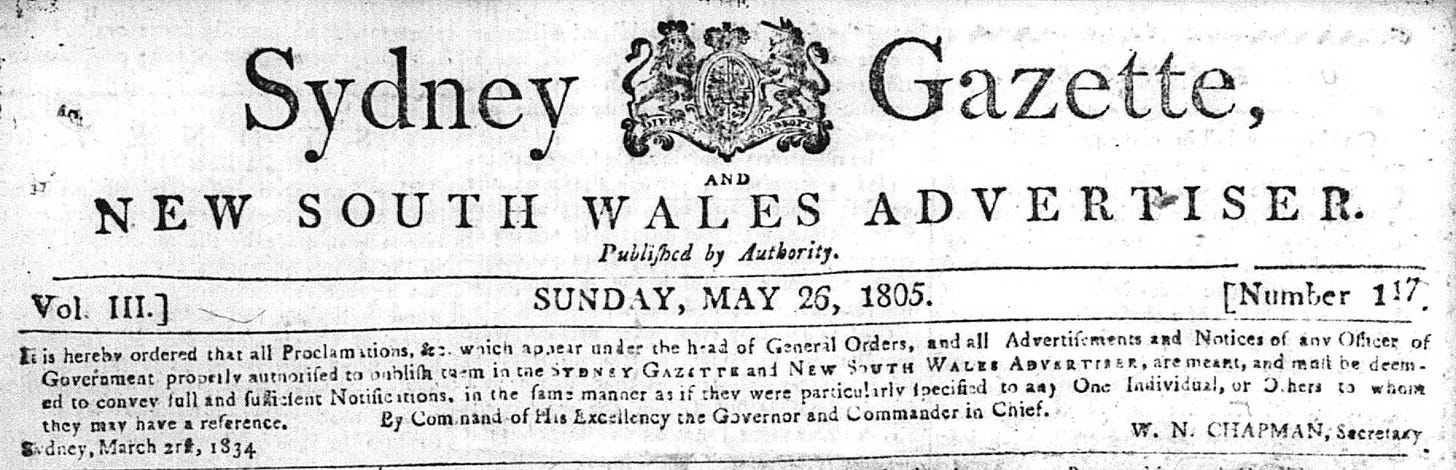

A couple of wild stories from Australia’s first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette, from when the colony was just 15 years old on plus some other interesting tidbits. I will update with pictures and details and new stories as I have time.

MOOWATTYE: MAN ABOUT TOWN IN LONDON

In 1810, a botanist named George Caley took his guide and assistant Moowattye, a young Parramatta lad, for a trip to London where he was treated very kindly.

This was achieved with great difficulty as the British had a strict policy of discouraging anyone taking Aborigines or South Sea Islanders to Britain, for fear they would be mistreated or used as a circus curiosity.

Moowattye’s planned trip, however, was supported by Sir Joseph Banks, so he got to go. He was the third Aboriginal person to go to England after Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne, who went with Arthur Phillip, and were also treated with great hospitality.

Moowattye spoke very good English and was dressed in “the very pink of fashion”, and was reportedly very proud of his finery.

He stayed in Chelsea, in London’s trendy West End, where he frequented a “coffee house”, smoked a pipe and went to the theatre.

Most Londoners had never seen an Aboriginal man before, so everyone wanted to meet him.

The Gazette reported: “Moowattye attended every show he heard of, and generally appeared more surprised at the numbers of people assembled in a crowd than at any other circumstance.”

He was the talk of the town. But the magnificence of the buildings did not impress him.

“When once asked how he liked the fine shops and houses, he answered that they were all very good, but not equal to the woods in his own Country,” the Gazette reported.

A Gentleman at the coffee house urged Moowattye to encourage his tribe to alter their way of life “hoping above all things that he would not throw away his clothes”.

Moowattye took his pipe out, leaned over to speak directly in the Gentleman’s ear and said “If I should, I’ll send you word”.

When he was asked what he would like to take to his friends as a present, he said “something to eat”.

The amazing new array of foods brought by the English were consistently described as the most interesting thing to Aboriginal people about the new white tribe that had settled on their shores.

An English Gentleman gave him a fowling piece (gun) as a present, which Moowattye pledged to keep “for ever and ever”. On his return, aged 21, Moowattye sold it for seven and six-pence, and went back to live with his tribe.

Western life is not for everyone. It was a choice that appealed to some Aboriginal people but not others.

Sadly, this story does not end well.

Several years later, Moowattye brutally raped and beat Hannah Russell, a 15-year-old settler’s daughter on a public road near Parramatta. He dashed her head against a tree, and beat and bruised her all over. He was tried, convicted and hung for his crime, becoming the first Aborigine to be executed.

STEALING MELONS TOGETHER: WHITEYS and ABORIGINES

Growing food was the big priority in 1788. No food, no life.

It was a serious business with theft often punished by death.

Garden Island is now a naval base at Woolloomooloo, joined to the mainland, but back then it was a completely detached island.

The new colonists immediately turned it into kitchen gardens to provide for the officers and crew of First Fleet vessel HMS Sirius.

It has the first known colonial graffiti carved into the sandstone: “FM 1788” – believed to be steward of the Sirius, Frederick Meredith.

In one of the earliest editions, the Sydney Gazette reports on an inquest held over the death of an Aboriginal man at Garden Island.

The native man had been shot “while plundering the grounds of Captain Scott”. His canoe was found full of maize, melons and other goods, which Aboriginal people had not seen before British settlement.

But he did not act alone. Several other people had “assisted in the depredation” and when confronted by Captain Scott’s servants had escaped by jumping into the water.

“It also appeared, we are sorry to say, that several white men were among the natives who, there is every reason to suspect, had assisted and encouraged them in this delinquency,” the Gazette reported.

So there was plenty of co-operation, even when it came to crime.

SNAKE BITE CURE

In 1819, the Sydney Gazette reported that a soldier was bitten by a snake near Liverpool. His body began to swell in a few minutes and he was given up for dead.

An old native man at the barracks stripped shreds of bark from a tree and tied a ligature above the bite so tight “that the patient supposed his leg had been taken off”.

He rubbed the leg downwards then cut the skin around the puncture marks off and sucked out “coagulated matter”.

“The man now lives; and in gratitude to his black physician gave him all he was possessed of, being to the value of about £5 sterling.”

Five pounds was a small fortune back then.

AUSTRALIA’S OLDEST BRIDGE

Australia’s oldest bridge is in the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney

Macquarie Culvert, in the Botanic Gardens, is the oldest surviving bridge. The tiny bridge was built in 1816 by Governor Lachlan Macquarie around the Government Domain.

It was part of a road made for the convenience of his wife, Elizabeth, who he was devoted to.

The road has gone but the culvert and a protective wall are still there, and you can see convict chisel marks on the sandstone blocks.

There is great detail on the surprisingly interesting history of the drainage and sewerage systems from 1788 to 1857 in a journal article HERE written by a wonderfully intelligent scholar named Anna Wong, who I had the privilege of knowing at Sydney Uni where we both did Arts Degrees.

There is no sign to tell you this is Australia’s oldest bridge but you can find it near the duckponds and café.

THE PINTUPI NINE WALKED OUT OF THE DESERT IN 1984

The last uncontacted Aboriginal people, the Pintupi Nine, walked out of the Gibson Desert in 1984 to meet their relatives in Kiwirrkura, near Kintore.

They had never seen glass. They had never seen a motor car. Running water from the tap was a wonder after harsh desert survival.

My former boss at NT News, Nigel Adlam, had written one of the first stories on them, and met them, he said. Here is a story that I suspect is by him, not sure why the byline says Nigel Adam instead.

“Warlinipirri, his three brothers, Walala, Thomas and Yari Yari, three sisters, Yardi, Yikuljti and Tjakaraia, and two "mothers", Nanyanu and Papalanyanu, were the last Aborigines living a traditional nomadic existence,” he wrote.

“They became known as the Pintupi Nine.”

They were angry with their relatives for not telling them about the supermarket and easy living.

Adlam wrote that when the family were driven from the doctor at Kintore 27km to the smaller community of Kwiwikurra, the nomads ritually beat members of their extended families with sticks for not bringing them in from the desert earlier.

But Western settlement isn’t for everyone. One of the Pintupi Nine returned to the nomad life.

Yari Yari, lived at Kwiwikurra for two years before slipping back into the desert.

BENNELONG, COLEBEE and CAPTAIN ARTHUR PHILLIP

Note: I have to dig out the Sydney Gazette references for this one, this is mostly from modern sources

When the British first landed to set up a colony in 1788, they were under strict instructions to befriend Aboriginal people and not to treat them badly.

“You are to endeavour by every possible means to open an intercourse with the natives and to conciliate their affections, enjoining all Our Subjects to live in amity and kindness with them,” relayed King George in a letter dated 25 April 1787, as Australian Geographic reports.

Captain Arthur Phillip tried his best but it was so hard to establish contact. The tribesmen were wary and kept away.

Desperate to communicate, Captain Phillip managed to kidnap two Aboriginal men, Bennelong and Colebee, in November 1789.

The idea was to teach them English so they could translate messages and explain their culture and customs.

Colebee soon escaped so Woollarawarre Bennelong was kept in shackles for the first few months.

In 1790 they reduced the restrictions on him and he escaped, too, leaving Captain Phillip back at square one.

Four months later, Bennelong was spotted at Manly Cove feasting on a whale carcass with about 20 warriors.

Bennelong gestured to another Aborigine, Willemering, and Captain Phillip misunderstood.

He thought it was an invitation to be introduced, so he held out his hand for a handshake.

But Willemering speared him in the shoulder as payback for kidnapping Bennelong.

A fight nearly broke out but Captain Phillip forbade any return violence and the officers took their injured captain to safety.

Bennelong then came to visit him as he was recovering and befriended him. The captain built a hut for him on Bennelong Point, the site of the Opera House today.

An extraordinary and tumultuous friendship evolved between the pair: Arthur Phillip was struggling to make sense of an alien world, and Bennelong helped him navigate it.

They had their ups and downs.

When soldiers shot an Aboriginal man stealing potatoes near Dawe’s Point in December 1790, Bennelong was furious: it was his friend Bangai who was killed. Bennelong started robbing settlers and demanding Captain Phillip reveal the name of the soldier who shot his friend for payback.

But by 1791 the pair had reconciled.

Bennelong became Captain Phillip’s interpreter and travelled with him to Britain in 1792, along with another Aborignal man Yemmerrawanne, the first known visit by Aboriginal people to England.

They visited St Paul’s Cathedral, the Tower of London, and possibly met the king.

Yemmerrawanne became ill and died in Britain of a chest infection.

Bennelong’s health also deteriorated so he returned to Sydney in 1795 and was nursed back to health.

In 1797, Colebee killed another Aboriginal man during tribal feuding and was punished with violence according to Aboriginal custom. Not understanding, British soldiers interfered to protect Colebee – once again this enraged Bennelong.

Bennelong threw a spear at the soldiers, severely wounding one through the abdomen.

A British soldier dragged Bennelong away for his own safety as the other soldiers would have killed him. He was locked up for the night and on being released he threatened the white people, left the settlement and declared he would spear the Governor when he saw him.

He died in 1813 at Kissing Point where he had become the leader of the dispossessed Port Jackson clans who had moved to the north side of the Parramatta River.

He was buried in the orchard of his white friend, brewer James Squire, but was still hated by the colonists for turning against him.

In 2011 this grave was found at 25 Watson Street, Putney. The NSW Government bought the house to preserve it as a memorial, as ABC reported.

Colebee and another Aboriginal leader named Nurragingy, ended up loved by the colonists and Governor Lachlan Macquarie gave them a land grant of 30 acres on the corner of Richmond Rd and Rooty Hill Rd in 1819.

Thanks especially for the numbers in another post about the corporate money funding the Yes campaign.

Shows the dereliction of the (ex-) Left that Amnesty warn Survival Day (sic) attendees to wear the useless blue splashguards because of "Covid."

But Alison writes: "Yemmerrawanne became ill and died in Britain of a chest infection."

There is no evidence of infection/contagion and of germs.

The Aust. natural healther Daniel Roytas has just published "Can you catch a cold?" and concludes after 4 years trawling through 100+ years of medical lit that you cannot. (Pity that Roytas seems reluctant to ever talk in public about events from 2020 to date but at least Sam Bailey writes the foreword to his book)

And Dr Yeadon, ex-Pfizer who used to head up Global Respiratory Viruses, now says : 1 there are no viruses. 2. there are thus no pandemics and cannot be.

He stresses that our beliefs in 1 and 2 are needed for us to continue being fooled by the enemy into any procedure that keeps us "safe": lockdowns, social distancing, and of course endless jabs.

Thanks Alison you’re a great writer. Some of the stories are well known but raising them at the right time makes them more powerful.